16.

The head of Lancastrian forces at Barnet was Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick (which, in honorable British tradition, we pronounce Warrick). He was called Kingmaker because after the death of his father he was the most influential land owner in England and lent his miltary support toward making his cousin, Edward IV, King of England.

Whichever side he would have been on, he was considered a force to be reckoned with.

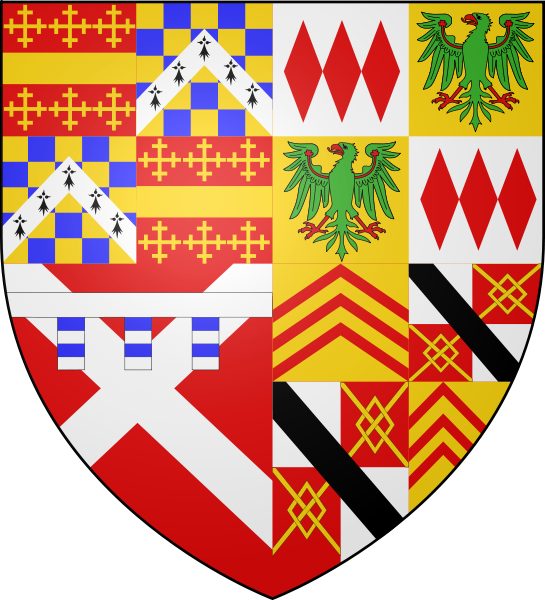

While researching blazons (which we will remind are the concise and exact textual descriptions of coats of arms) Nevilles is one of the first. Now, rolls of arms such as the one pictured in the blog's header here can be fairly simple to lay out. A simple grid. But, like the presence of Warwick changed the terms of the battle, the presence of Warwick's coat changes the terms of the layout. Here's his coat:

Whole lot of stuff going on then, yes?

What you are looking at there is a little scheme called quartering, which seemed to be typically done to represent claims to family lines. In this case, the good Earl's arms say that he is heir to no less than six family lines outside of his own (which is represented by the lower left hand quarter, the only one with a single coat design). Outside of that lower left quarter it should be noted that each quarter is quartered further to unite two family's coats into a single design each; each one of these are grand quarters.

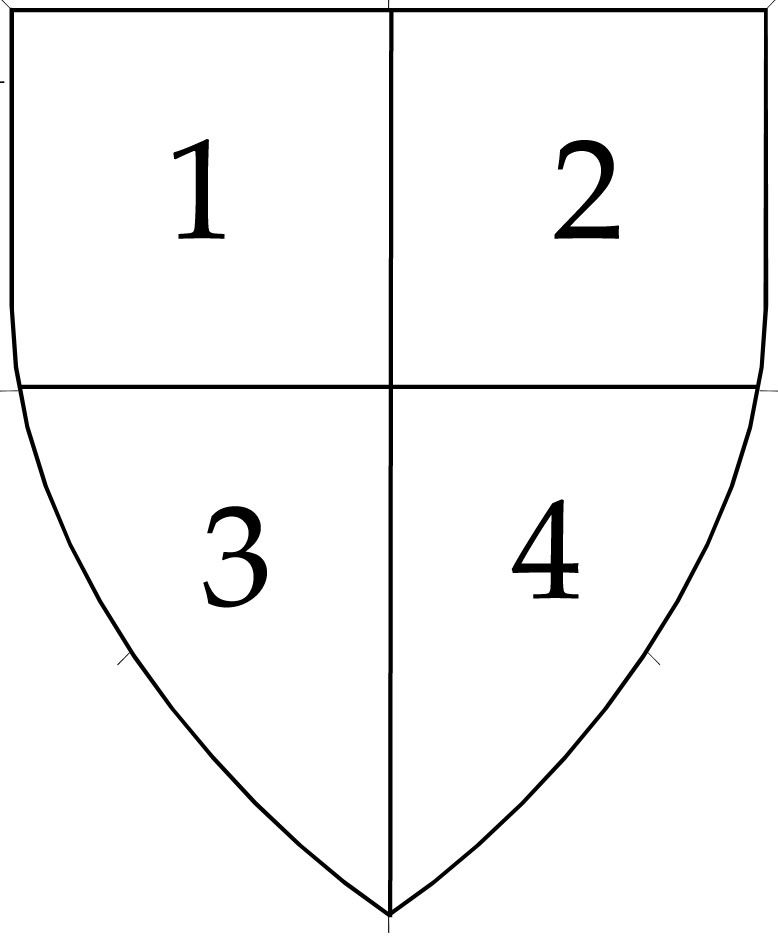

In identifying each quarter it is helpful to keep the following diagram in mind:

This is the way we identify quarters in blazon. We say 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Quarters. Basically rather simple in concept. The grand quarters are similarly divided.

Making a long story short, here's the rundown (facts gleaned via The General Armory of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, p. 727, by Sir Bernard Burke, C.B., LL. D., Ulster King of Arms, ISBN 0-7884-0558-6, published in 1996 by Heritage Books:

- In the first grand quarter, we have the coats for Beauchamp (pronounced "beecham") and Clare. The convention here is when two families arms are displayed in quarters, the first name mentioned is the coats in 1st and 4th quarters, the second name is 2nd and 3rd. So Beauchamp is in the upper right and lower left, and Clare is in the upper left and lower right.

- In the second grand quarter, the coats for Montagu (or Montacute in the Armory) and Monthermer.

- In the third grand quarter we find the personal arms of Richard Neville.

- In the fourth grand quarter are the arms for Warwick and Le Despencer.

If the reader will permit me to indulge in a bit of blazon, just for the sake of practice:

- Beauchamp: Gules, between six crosses crosslet a fess Or.

- Clare: Cheky Or and azure, a chevron ermine.

- Montagu: Argent, three lozenges gules.

- Monthermer: Or, an eagle vert, armed gules (notably the eagle is in German style, with the wings typical of that style ... the curved detail within the wing ending in a small cloverleaf shape is called kleestengl, and is reputed to be a stylization of the wing bones)

- Richard Neville: Gules, a saltire argent, overall a label of three points. (note: my blazon is rather weak here. British tradition seems to hold some significance in decorating the label, which explains why those blue bars are on the label's points, but I have no idea what they mean. More on the label ... which is that band with the three ribbons hanging down, later). Another way to say this would be recursively: Neville differenced by a label of three points, which simplifies the blazon significantly but, lacking the illustration, requires research to find out what the original Neville arms were (in this case, the white X on the red field).

- Warwick: Or, three chevronels gules.

- Le Despencer: Quarterly, argent and gules, a fret Or, overall a bend sable.

Reviewing the previous posts in this blog, I note that I've said not all that much on the colors and shapes (or as armorists say, tinctures and ordinaries ) contained therein. This may be a good time to lay out some ground rules on that as well as I know them, but that should be reserved, I think, for the next discourse. This one has gone pretty far afield as it is.

Back to what was putatively the subject of this post. The viewing of Warwick's arms changes the rules here. We have made some preliminary estimates of layout and design which are being reconsidered. The mere complexity of Warwick's coat makes obvious that we cannot simply do a small coat or a coat that is the same size as other coats. Since we are going to be doing this in tempera on parchment this will be an adventure indeed.

And, my instructor reminds me, we will be doing two copies. And in the Middle Ages, there were no Kinko's. So once we create one, we will be creating another.

But this does open rather exciting new avenues for layout possibilities, if only because we can, for example, make Warwick's coat the centerpiece of a layout and array his supporter's coats about them in a style suggestive of who followed who.

But regardless of his complexity we can at least be thankful that he's not Lloyd of Stockton, which famously has 323 quarterings (see Ottfried Neubecker's Heraldry: Sources, Symbols and Meaning, ISBN 1-85501-908-6, pub. 1997, Tiger Books, London, page 95 in all its gory glory) or the 719 quarterings of the arms of the Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville family, which can be seen in the Wikipedia entry on Quarterings (or you can just go straight to this dog's breakfast, lunch and dinner here ... but a warning, it's ooooogly!)

References:

- The General Armory of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales, Sir Bernard Burke, C.B., LL.D., Ulster King of Arms. ISBN 0-7884-0558-6, 1998, Heritage Books

- Heraldry: Sources, Symbols and Meaning, Ottfried Neubecker, ISBN 1-85501-908-6, 1997, Tiger Books

- Wikipedia article on Heraldic Quartering, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quartering_(heraldry)

- Wikipedia article on Richard Neville, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Neville%2C_16th_Earl_of_Warwick

Important Note On Wikipedia references:

We do not suggest that Wikipedia references are utterly dependable, but we do use them for conveniences sake after we have been satisfied that they do not contain erroneous information. For instance, we have confidence that the entry on Neville has correct arms, since this agrees with what Burke's Armory has.

Tags: Richard Nevill, Earl of Warwick, Heraldry, Quartered Coats, Battle of Barnet, The Kingmaker

Powered by Qumana